Modern Sibelius

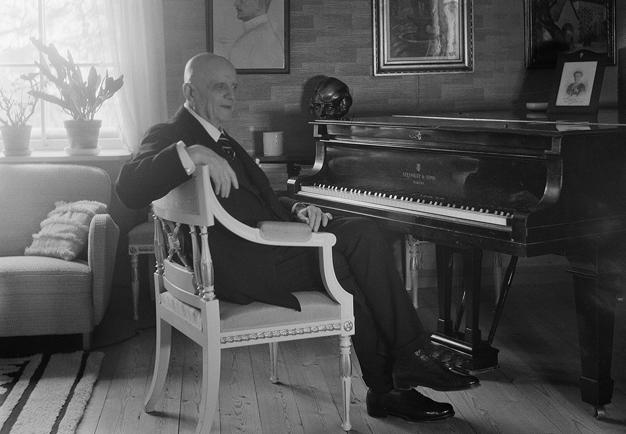

Jean Sibelius, at home

The composers’ composer: what is the attraction behind the façade and under the skin of Sibelius' music? We take a closer look at the unique aspects that have made Jean Sibelius hip and admired in the most unexpected circles.

It is often said that Sibelius did not form a school, meaning that there are no clear successors. That may be the case, but his influence is great – not least in modern times, which may surprise some. After all, if Sibelius was already considered something of a traditionalist during his lifetime, what could he have to say to composers after his death? Quite a lot, it turns out. Those who once dismissed Sibelius’ compositions as belonging to a bygone world were simply wrong: they looked at the building, the exterior so to speak, but did not appreciate the original constructions inside and behind the façade.

So when the German sociologist and philosopher Theodor W. Adorno contemptuously called Sibelius a “scribbler”, it may well be because he lacked the right tools, and saw Sibelius’ divergences as failures.

”If Sibelius is good, then the musical criteria that have been applied from Bach to Schoenberg are invalid,” Adorno wrote. A different kind of reading was needed to analyse and appreciate Sibelius’ language, grammar and sentence structure.

But Sibelius' music isn’t exactly hard to listen to? No, on the contrary, the music is usually accessible and attractive to a very wide audience. That’s the exterior. But it is in the thinking about form that Sibelius’ true originality emerges, in his work with small motifs that are linked together and grow and change into new incarnations. It is the small things that eventually determine the big things, and this often happens almost imperceptibly and in an extremely refined way.

This gives Sibelius’ music a striking sense of organic material; a kind of physicality – or natural quality. From the description of such techniques it is not difficult to understand why people such as the greatest contemporary American composer, John Adams (honoured at Konserthuset’s Composer Festival in 2005), has so often spoken of his love for Sibelius: from a bird's eye view, the whole line of Adams’ development as a composer is like a story about Sibelius’ formal language, from Adams’ early minimalist work with small, repetitive motifs to the large, organic forms of operas and huge orchestral works of today.

The tonal colour of Sibelius’ work should be added to its originality. Sibelius was a synesthete (meaning he had the ability to correlate different sensory impressions) and saw colours in tones, and tones and sounds in colours. It is said that he also heard sounds through smells. And although Sibelius’ music is generally not overtly bold in harmonic terms, there are special qualities and departures from major/minor tonality here too, which, together with his personal blending of instruments, sounds and textures, give rise to a very special resonance of vibrant colour in Sibelius’ music.

So, no, it’s no wonder that composers like Gérard Grisey and Tristan Murail in what was known as the French spectral school of the 1970s – composing based on the advanced analysis of sounds and the overtone spectras of sounds – also bowed in admiration at what they heard in Sibelius, the “scribbler”. This was the case when for example they listened to the Seventh Symphony, which the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra had premiered under the composer’s direction in 1924; a symphony, incidentally, that Anders Hillborg quotes in Exquisite Corpse, a work commissioned by the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra and first performed in 2002.

Tony Lundman